As I recall, it was a warm North Dakota summer day. I was either six or seven. The war was over, and my dad still owned the Standard gas station on Lincoln Avenue, the main drag of my hometown on the Soo Line south of Minot. My dad sold the station in l947, so my little excursion with my mother took place after the end of the war and before l947. We were bringing my dad his noontime lunch, a daily activity, since my dad usually did not have a helper and was alone at the station. He depended on us to bring his meals, dinner and supper, even in the dead of a cold North Dakota winter.

Our house was near the Soo Line tracks, but we lived on the south side, a distinction that back then seemed very important. Even though my aunt and uncle lived on the north side of the tracks, we somehow felt more entitled, to what I have no idea, and, of course, we never mentioned it to Elsie and Ernie, my dad’s sister and husband. When my mom and I walked north two house and made a left turn, we were just two blocks from the Standard station.

The meticulously kept house on the corner was owned by two German sisters, who kept the most beautiful garden in town. Those two Catholic saints would walk by our house every morning very early on their way to mass at the local Catholic church about 3 blocks away. Every time, my mother would mention, “You know, Curtis, Germans are known for being great gardeners.” To this very day, I still believe this stereotype about Germans.

The next house behind the gardeners’ belonged to the Whitmans. They ran a bar across the street from my dad’s business. In the twenty odd years that I lived in Harvey, I saw them only a few times. I didn’t frequent their bar, and when they weren’t working, they must have slept all the time. But I can still remember his first name–Joe. Still trying to think of her name. I don’t think they had any children.

On these walks, we would glance over to our right to the two or three small storage buildings or sheds that ran alongside the Soo Line tracks. In that area close to the train depot, there were six to eight tracks. Late evenings and during the middle of the night I would hear the trains switching, clanging and banging away, a sound that lulled me to sleep. I love the sound of a train. It is built into my DNA.

We would usually carry coffee in a glass jar to my dad. No Starbucks back then. But this was a sweltering summer day, very unusual for North Dakota, so we probably brought him some nectar, a sweet drink similar to Cool Aid but much better. In the bag that my mom carried was probably a sandwich of some kind and either cookies or cake. By now we had reached a corner and walked across the gravel street to block number 2.

This was usually the most interesting part of the trip for me because on the corner was an old house where my parents had had an apartment the year I was born. I came into this world in the Harvey Hospital, but that house was so fascinating to me. That was where I had spent the first two years of my life. I had seen pictures of me on a nice day sitting outside in my high chair eating. There were pictures of me with my mother’s mother holding me. She had died earlier that year after having spent the last year of her life living with us in our cramped little house. I can now pinpoint the year of this trek to the Standard station. It has to be 1946, since my grandmother died in April of ’46.

Right behind that house was the local blacksmith shop. I find it so interesting to realize that I grew up in a small town that still had a smithy. My memory tells me that the front door was always open, even in the middle of the winter, and hot, acrid air would escape through that open door. I know that during the war my parents scowered the two junkyards in town trying to find parts to assemble a tricycle for me. I know that this blacksmith was responsible for that trike that I pedaled up and down our street for several years. A few yards behind the blacksmith shop was our destination and my hungry dad.

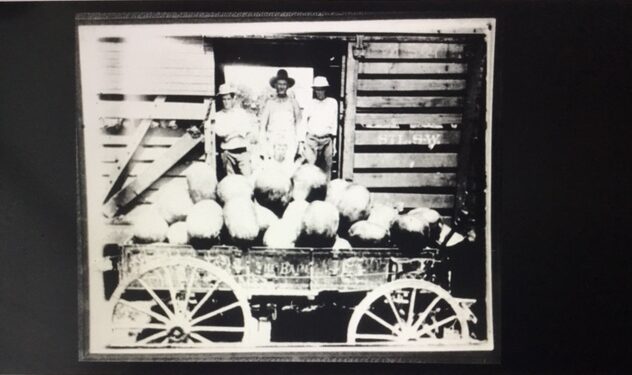

But something totally unexpected happened that day. Before we reached the Standard Oil station with its red and blue glass-topped pumps, I looked across the street to where a railway siding held an open rail car with watermelons peering over the top. Now, what kid doesn’t like watermelon, especially on such a hot day? I started tugging at my mom’s hand, urging her to go across the street and buy a melon. But, instead of following my lead, she jerked me back and said she did not want to buy from those men.

Those men were “darkies,” riding the rails and selling watermelons along the way. I had paid no attention to how these young men looked. I had seen pictures, of course, of Negroes. However, I had never seen one in person. My mother was a quiet, soft-spoken, kind woman who rarely made a fuss about anything. I was surprised by her quick actions to get me back on the sidewalk to complete our walk. Even at age 6, I sensed something had disturbed her. But what? I think it was at that point that I took a closer look at these men, their dark skins shining in the noonday sun. I realized that they looked so different from the pale Scandinavians in my family.

My mother had graduated with a two-year teaching degree from Minot State Teachers College. She had taught in country schools for about 7 years before I was born. She had taught me to read and write before I began first grade. She had no idea that she had just taught me another lesson, this one about bigotry, prejudice, and stereotyping. But, let’s remember that this is l946 in rural North Dakota. I would turn 7 that September. I was a smart kid who had been taught many important lessons by my teacher- mother. She was still teaching me. As an English instructor at a community college, I taught an essay entitled “People Are Not Born Prejudiced.” I knew that my mother, like all of us, are taught to be prejudiced. My mother was never aware of the impact that this walk to my dad’s Standard Oil station has had on me. The fact that now, seventy-six year later, I am writing this remembrance speaks to the power that this experience still has over me.

My dad received his much-deserved dinner that noon. That evening my mom and I would bring him his hot supper. His reward for our two-block walk was to have his tummy fed. What did I gain? I am still on that long two-block walk I am searching, looking for answers to reverse a lesson that my mother never wanted to teach me. But I keep walking and searching. It has been a long transformative journey.

My mom and dad never got to know their three great-grandsons, my grandsons, one of whom is Miles, adopted by daughter Anne and her husband when Miles was just newborn. Miles’ biological mother is an African-American lady from Atlanta. Miles, now 15, is a strong-willed and good-looking young man, resembling those young men selling watermelons off a rail car on a hot summer day those many years ago.

Copyright © 2024 by Curt Mortenson

Curt, your beautiful last sentence brought tears to my eyes. Thank you so much for a wonderful story. Ann Sigford

Hi Ann—Thank you for responding to my story. As a writer yourself, you know the value that feedback can have. It somehow validates our writing. And thank you for sharing your life stories. Keep writing! Curt Mortenson