In my junior year of college, I found an opportunity as a foreign exchange student to spend a semester in Denmark. I was part of a large group of exchange students that traveled to Copenhagen in January of 1973.

My International Politics class was a required class. It was held in a large auditorium with a few hundred students. An older man lectured; I did not know who he was.

One day he stated that there had been NO resistance to the Nazis in all of Europe during World War II. At all. Ever. All of Europe.

I raised my hand. I was angry about his statement, yet nervous because few people spoke out in this class.

The instructor listened as I mentioned resistance in Denmark, Sweden, and France. I waited for his response. Maybe he would question my historical facts. Instead, he only asked one question: “What is your name?” And then nothing.

I told him my name and almost immediately I realized — with a big gulp – that maybe I was in deep trouble. But I was fired up and not ready to back down. On reflection, I might have given him a false name, but I did not do this. I could feel the tension in the room and wondered what I had stepped into. No one spoke to me afterwards.

That night I mentioned this exchange with the teacher to my Danish surrogate mother. She asked what the professor’s name was. I told her. “Oh!” she said. “He’s a big local news anchor, a celebrity in Copenhagen.” I knew that, at the very least, I had bruised his ego. She assured me that it would be OK. I was surprised that in progressive Denmark, less than 30 years after WW II, that I would feel the sting of a Nazi sympathizer there.

What was the consequence of my speaking out? Instead of receiving a letter grade in the class, like my fellow students, I unexpectedly received a “Pass” on a “Pass/Fail” scale. I was confused by this. Then I realized I must have been spared a low grade from the instructor by receiving a “Pass” instead. Someone, unknown to me, had the courage to intervene on my behalf.

There was historical precedence in my family for speaking out. My father had the courage to be a Conscientious Objector in World War II. He served in the Civilian Public Service for the duration of the war: first, in Swamp Reclamation in Mississippi, and then in the Fairfield Mental Hospital in Connecticut. Out of 12 million draftees, 12,000 served in CPS. I felt I honored his courage to stand up and to stand alone.

I also had a good friend whose parents had survived concentration camps during World War II. I first knew her in elementary school. When we were in high school, her mother spoke for the first time about her experiences in a concentration camp. I did not want their horror, their courage, to go unnoticed, unacknowledged. No doubt that was part of the reason I spoke out in the International Politics class.

My college experience in Denmark has motivated me throughout my life to have the courage to speak out when I have felt it was right to do so.

One of my favorite quotes is from the German writer Goethe: “Be bold and mighty forces will come to your aid.”

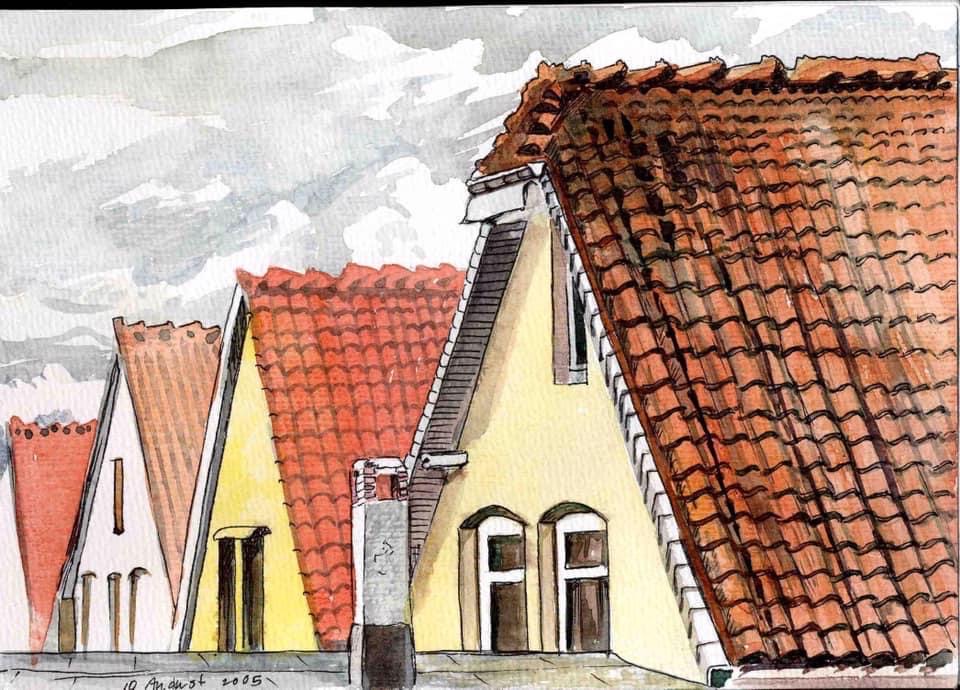

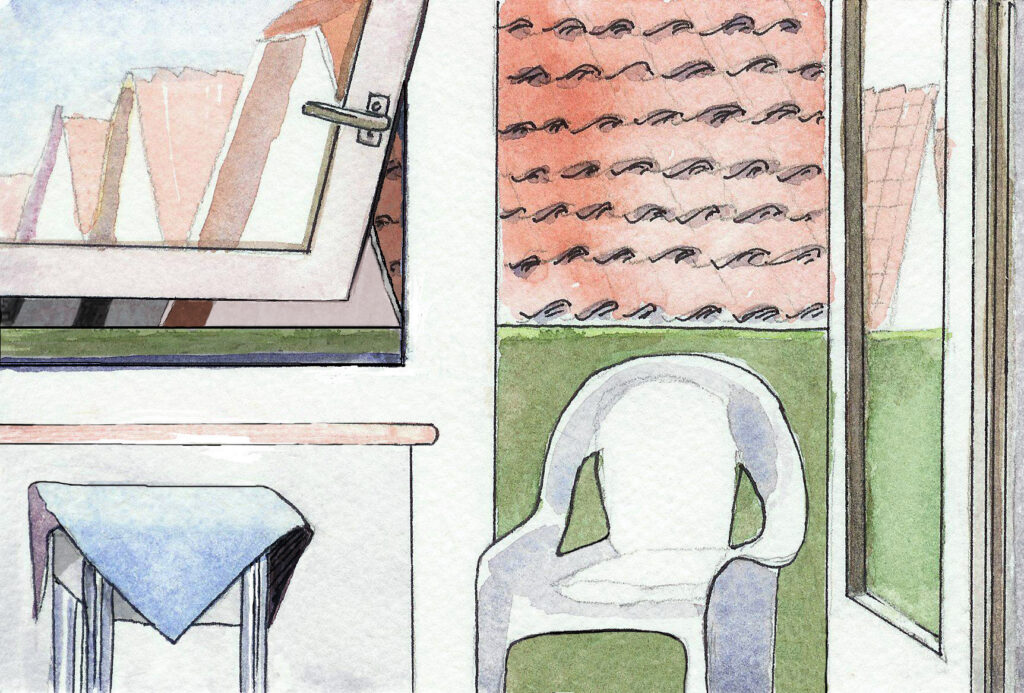

Editor’s Note: The artwork in this post was done by Addie during her stay in Europe in 2005. Water color and ink for media.

Copyright © 2024 by Addie Seabarkrob

Thank you for sharing such a poignant memory, especially sad as today’s rhetoric blares through the media. The watercolor and ink artwork is delightful.

Thank you Ann, I agree with this being timely still. Thanks for the appreciation of the watercolors too. ❤️